Many custom options...

And formats...

In Flowers the Cherry Blossom in Men the Samurai in Chinese / Japanese...

Buy an In Flowers the Cherry Blossom in Men the Samurai calligraphy wall scroll here!

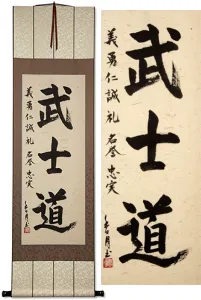

See also: Bushido - Code of the Samurai Warrior

In Flowers the Cherry Blossom, In Men the Samurai

This Japanese proverb simply reads, “[In] Flowers it's Cherry Blossoms, [In] Men it's Warriors.”

花は櫻木人は武士 is meant to say that of all the flowers in the world, the cherry blossom is the best. And of all men in the world, the Samurai or Warrior is the best

This proverb has been around for a long time. It's believed to have been composed sometime before the Edo Period in Japan (which started in 1603).

Some will drop one syllable and pronounce this, “hana wa sakura hito wa bushi.” That's “sakura” instead of “sakuragi,” which is like saying “cherry blossom” instead of “cherry tree.”

The third character was traditionally written as 櫻. But in modern Japan, that became 桜. You may still see 櫻 used from time to time on older pieces of calligraphy. We can do either one, so just make a special request if you want 櫻.

Note: Because this selection contains some special Japanese Hiragana characters, it should be written by a Japanese calligrapher.

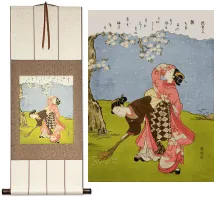

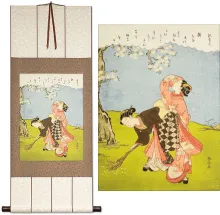

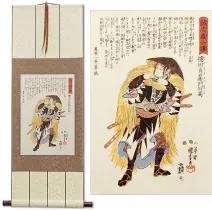

This in-stock artwork might be what you are looking for, and ships right away...

Gallery Price: $96.00

Your Price: $52.88

Gallery Price: $108.00

Your Price: $59.88

Gallery Price: $115.00

Your Price: $63.88

Gallery Price: $108.00

Your Price: $59.88

Gallery Price: $108.00

Your Price: $59.88

Gallery Price: $108.00

Your Price: $59.88

Gallery Price: $200.00

Your Price: $118.88

Gallery Price: $108.00

Your Price: $59.88

Gallery Price: $200.00

Your Price: $118.88

Gallery Price: $108.00

Your Price: $59.88

Gallery Price: $108.00

Your Price: $59.88

Gallery Price: $108.00

Your Price: $59.88

Gallery Price: $108.00

Your Price: $59.88

Not the results for in flowers the cherry blossom in men the samurai that you were looking for?

Below are some entries from our dictionary that may match your in flowers the cherry blossom in men the samurai search...

| Characters If shown, 2nd row is Simp. Chinese |

Pronunciation Romanization |

Simple Dictionary Definition |

花は桜木人は武士 see styles |

hanahasakuragihitohabushi はなはさくらぎひとはぶし |

(expression) (proverb) the best flowers are the cherry blossoms, the best individuals are the samurai; as the cherry blossom is first among flowers, so is the samurai first among men |

Variations: |

hanahasakuragihitohabushi はなはさくらぎひとはぶし |

(expression) (proverb) the best flowers are the cherry blossoms, the best individuals are the samurai; as the cherry blossom is first among flowers, so is the warrior first among men |

Variations: |

hanahasakuragi、hitohabushi はなはさくらぎ、ひとはぶし |

(expression) (proverb) the best flowers are the cherry blossoms, the best individuals are the samurai; as the cherry blossom is first among flowers, so is the warrior first among men |

The following table may be helpful for those studying Chinese or Japanese...

| Title | Characters | Romaji (Romanized Japanese) |

| In Flowers the Cherry Blossom, In Men the Samurai | 花は櫻木人は武士 花は桜木人は武士 | hana wa sakuragi hito wa bushi |

| In some entries above you will see that characters have different versions above and below a line. In these cases, the characters above the line are Traditional Chinese, while the ones below are Simplified Chinese. | ||

Successful Chinese Character and Japanese Kanji calligraphy searches within the last few hours...