Many custom options...

And formats...

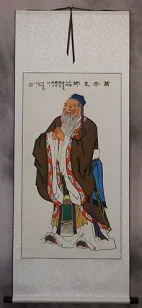

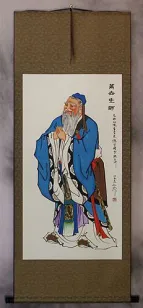

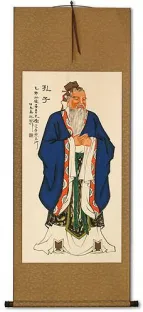

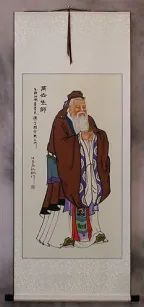

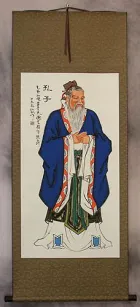

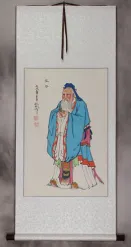

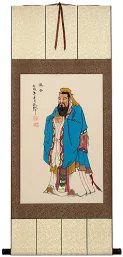

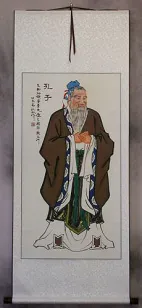

Confucius in Chinese / Japanese...

Buy a Confucius calligraphy wall scroll here!

Personalize your custom “Confucius” project by clicking the button next to your favorite “Confucius” title below...

1. Confucius

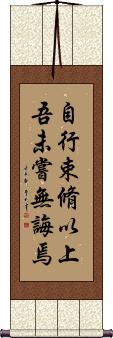

2. Confucius: Universal Education

3. The Five Tenets of Confucius

4. Confucius: Golden Rule / Ethic of Reciprocity

5. Benevolence

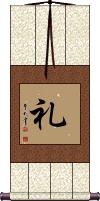

7. Respect

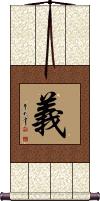

8. Justice / Rectitude / Right Decision

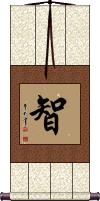

9. Wisdom

10. The Foundation of Good Conduct

11. Learning leads to Knowledge, Study leads to Benevolence, Shame leads to Courage

13. Forgiveness

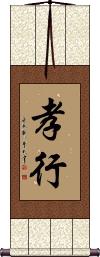

15. Filial Piety / Filial Conduct

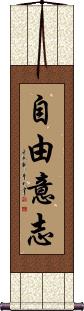

16. Free Will

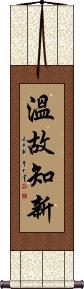

17. Learn New Ways From Old / Onkochishin

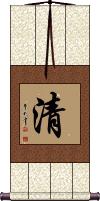

18. Clarity

19. One Justice Can Overpower 100 Evils

20. Daoism / Taoism

22. Great Aspirations / Ambition

24. Filial Piety

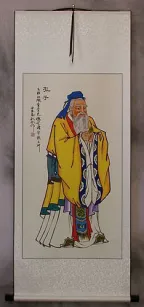

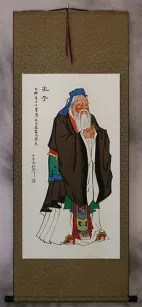

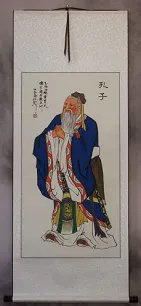

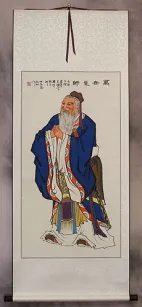

Confucius

孔子 is how to write the name of the great sage, known in the West as Confucius.

His real name is Kongzi (The name Confucius is a westernized version of his name - his family name is Kong, and “zi” was added as a title of distinction).

He lived some 2500 years ago in Qufu, a town in modern-day Shandong Province of Northern China (about 6 hours south of Beijing by bus). He was a consort to Emperors, and after his death, the impact of his philosophies still served to advise emperors, officials, and common people for generations.

Also during these thousands of years, the Kong family remained powerful in China, and the Kong estate was much like the Vatican in Rome. The Kong estate existed as if on sovereign ground with its own small garrison of guards and the privileges of a kingdom within an empire.

This was true up until the time the Kong family had to flee to Taiwan in 1949 when the Red Army took victory over the Nationalists during the Revolution. The home of Confucius was later razed and all statues were defaced or stolen during the Cultural Revolution. Finally, after years of smearing his name and image, it is once again okay to celebrate the teachings of Confucius in mainland China.

Known as Khổng Tử in Vietnamese.

Confucius: Universal Education

自行束脩以上吾未尝无诲焉 means, for anyone who brings even the smallest token of appreciation, I have yet to refuse instruction.

Another way to put it is: If a student (or potential student) shows just an ounce of interest, desire, or appreciation for the opportunity to learn, a teacher should offer a pound of knowledge.

This quote is from the Analects of Confucius.

This was written over 2500 years ago. The composition is in ancient Chinese grammar and phrasing. A modern Chinese person would need a background in Chinese literature to understand this without the aid of a reference.

The Five Tenets of Confucius

The Five Cardinal Rules / Virtues of Confucius

仁義禮智信 are the core of Confucius's philosophy.

Simply stated:

仁 = Benevolence / Charity

義 = Justice / Rectitude

禮 = Courtesy / Politeness / Tact

智 = Wisdom / Knowledge

信 = Fidelity / Trust / Sincerity

Many of these concepts can be found in various religious teachings. It should be clearly understood that Confucianism is not a religion but should instead be considered a moral code for a proper and civilized society.

This title is also labeled “5 Confucian virtues.”

![]() If you order this from the Japanese calligrapher, expect the middle Kanji to be written in a more simple form (as seen to the right). This can also be romanized as "jin gi rei satoshi shin" in Japanese. Not all Japanese will recognize this as Confucian tenets but they will know all the meanings of the characters.

If you order this from the Japanese calligrapher, expect the middle Kanji to be written in a more simple form (as seen to the right). This can also be romanized as "jin gi rei satoshi shin" in Japanese. Not all Japanese will recognize this as Confucian tenets but they will know all the meanings of the characters.

See Also: Ethics

Confucius: Golden Rule / Ethic of Reciprocity

Do not do to others what you do not want done to yourself

Some may think of this as a “Christian trait,” but actually, it transcends many religions.

This Chinese teaching dates back to about 2,500 years ago in China. Confucius had always taught the belief in being benevolent (ren), but this idea was hard to grasp for some of his students, as benevolence could be kind-heartedness or an essence of humanity itself.

When answering Zhong Gong's question as to what "ren" actually meant, Confucius said:

己所不欲勿施于人 or "When you go out, you should behave as if you were in the presence of a distinguished guest; when people do favors for you, act as if a great sacrifice was made for you. Whatever you wouldn't like done to you, do not do that thing to others. Don't complain at work or home.”

Hearing this, Zhong Gong said humbly, “Although I am not clever, I will do what you say.”

From this encounter, the Chinese version of the “Golden Rule” or “Ethic of Reciprocity” came to be.

The characters you see above express, “Do not do to others whatever you do not want to be done to yourself.”

See Also: Benevolence

Benevolence

Beyond benevolence, 仁 can also be defined as “charity” or “mercy” depending on context.

The deeper meaning suggests that one should pay alms to the poor, care for those in trouble, and take care of his fellow man (or woman).

仁 is one of the five tenets of Confucius. In fact, it is a subject that Confucius spent a great deal of time explaining to his disciples.

I have also seen this benevolent-related word translated as perfect virtue, selflessness, love for humanity, humaneness, goodness, goodwill, or simply “love” in the non-romantic form.

This is also a virtue of the Samurai Warrior

See our page with just Code of the Samurai / Bushido here

The Dao of Filial Piety

孝道 most clearly expresses the Confucian philosophy of filial piety.

Confucius taught that all should be respectful and obedient to their parents. Included in this idea is honoring your ancestors.

The second character is “dao/tao” or “the way” as in Taoism. You can say this title is “The Tao of Filial Piety” or “The Way of Filial Piety.”

Respect

Politeness, Gratitude and Propriety

礼 is one of the five tenets of Confucius.

Beyond respect, 礼 can also be translated as propriety, good manners, politeness, rite, worship, or an expression of gratitude.

We show respect by speaking and acting with courtesy. We treat others with dignity and honor the rules of our family, school, and nation. Respect yourself, and others will respect you.

Please note that Japanese use this simplified 礼 version of the original 禮 character for respect. 礼 also happens to be the same simplification used in mainland China. While 禮 is the traditional and original version, 礼 has been used as a shorthand version for many centuries. Click on the big 禮 character to the right if you want the Traditional Chinese and older Japanese versions.

Please note that Japanese use this simplified 礼 version of the original 禮 character for respect. 礼 also happens to be the same simplification used in mainland China. While 禮 is the traditional and original version, 礼 has been used as a shorthand version for many centuries. Click on the big 禮 character to the right if you want the Traditional Chinese and older Japanese versions.

This is also a virtue of the Samurai Warrior

See our page with just Code of the Samurai / Bushido here

Justice / Rectitude / Right Decision

Also means: honor loyalty morality righteousness

義 is about doing the right thing or making the right decision, not because it's easy but because it's ethically and morally correct.

No matter the outcome or result, one does not lose face if tempering proper justice.

義 can also be defined as righteousness, justice, morality, honor, or “right conduct.” In a more expanded definition, it can mean loyalty to friends, loyalty to the public good, or patriotism. This idea of loyalty and friendship comes from the fact that you will treat those you are loyal to with morality and justice.

義 is also one of the five tenets of Confucius's doctrine.

![]() There's also an alternate version of this character sometimes seen in Bushido or Korean Taekwondo tenets. It's just the addition of a radical on the left side of the character. If you want this version, click on the image to the right instead of the button above.

There's also an alternate version of this character sometimes seen in Bushido or Korean Taekwondo tenets. It's just the addition of a radical on the left side of the character. If you want this version, click on the image to the right instead of the button above.

This is also a virtue of the Samurai Warrior

See our page with just Code of the Samurai / Bushido here

Wisdom

智 is the simplest way to write wisdom in Chinese, Korean Hanja, and Japanese Kanji.

Being a single character, the wisdom meaning is open to interpretation, and can also mean intellect, knowledge or reason, resourcefulness, or wit.

智 is also one of the five tenets of Confucius.

智 is sometimes included in the Bushido code but is usually not considered part of the seven key concepts of the code.

See our Wisdom in Chinese, Japanese and Korean page for more wisdom-related calligraphy.

See Also: Learn From Wisdom

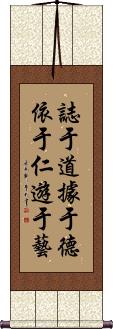

The Foundation of Good Conduct

Quote from Confucius

This proverb, 志于道据于德依于仁游于艺, from the Analects of Confucius translates as:

Resolve yourself in the Dao/Tao/Way.

Rely on Virtue.

Reside in benevolence.

Revel in the arts.

According to Confucius, these are the tenets of good and proper conduct.

This was written over 2500 years ago. The composition is in ancient Chinese grammar and phrasing. A modern Chinese person would need a background in Chinese literature to understand this without the aid of a reference.

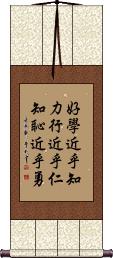

Learning leads to Knowledge, Study leads to Benevolence, Shame leads to Courage

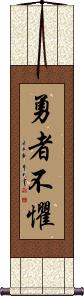

The Brave Have No Fears

This proverb means “Brave people [are] without fear,” or “The brave are without fear.”

勇者不懼 is a proverb credited to Confucius. It's one of three phrases in a set of things he said.

This phrase is originally Chinese but has penetrated Japanese culture as well (many Confucian phrases have) back when Japan borrowed Chinese characters into their language.

This phrase has also been converted into modern Japanese grammar when written as 勇者は懼れず. If you want this version just click on those characters.

See Also: No Fear

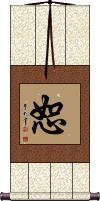

Forgiveness

恕 means to forgive, show mercy, absolve, or excuse in Chinese and Korean Hanja (though mostly used in compound words in Korean).

恕 incorporates the pictogram of a heart at the bottom, and a woman and a mouth at the top. The heart portion has the most significance, as it is suggested that it is the heart's nature to forgive.

In Asian culture, as with most other cultures, forgiveness is an act of benevolence and altruism. In forgiving, you put yourself in someone else's shoes and show them the kindness that you would want them to show you. Confucius referred to this quality as “human-heartedness.”

The Ease of the Scholar

Quote from Confucius

默而识之学而不厌诲人不倦何有于我哉 is a quote from the Analects of Confucius that translates as:

To quietly recite and memorize the classics,

to love learning without tiring of it,

never be bored with teaching,

How could these be difficult for me?

This is a suggestion that for a true scholar, all of these things come with ease.

This was written over 2500 years ago. The composition is in ancient Chinese grammar and phrasing. A modern Chinese person would need a background in Chinese literature to understand this without the aid of a reference.

Filial Piety / Filial Conduct

孝行 expresses the idea of filial piety or filial conduct.

While the first character means filial piety by itself, the second character adds “action.” Therefore this represents the actions you take to show your respect and obedience to your elders or ancestors.

Confucius is probably the first great advocate for filial piety.

Free Will

自由意志 is a concept that has existed for thousands of years that humans can understand right and wrong, then make a decision one way or the other (thus affecting their fate).

Sources such as Confucius, Buddhist scriptures, the Qur'an, and the Bible all address this idea.

As for the characters shown here, the first two mean free, freedom, or liberty. The last two mean “will.”

Can be romanized from Japanese as jiyū-ishi, jiyuu-ishi, and sometimes jiyuu-ishii.

It's 자유의지 or jayuu-yiji in Korean and zìyóu yìzhì in Chinese.

See Also: Freedom | Strong Willed | Fate

Learn New Ways From Old / Onkochishin

New ideas coming from past history

溫故知新 is a proverb from Confucius that is used in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean cultures.

It can be translated in several ways:

Coming up with new ideas based on things learned in the past.

Examine things of the past, and obtain new knowledge.

Developing new ideas based on the study of the past.

Gain new insights through restudying old issues.

Understand the present by reviewing the past.

Learning from the past.

Review the old and know the new.

Taking a lesson from the past.

Taking a lesson from the wisdom of the ancients.

Follow the old ways.

The direct translation would be, “By asking old things, know new things.”

The Character meanings breakdown this way:

溫故 = ask old

知新 = know new

Explained: To learn new things that are outside of your experience, you can learn from old things of the past. You can find wisdom in history.

Note: Japanese use a variant of the first Kanji in modern times.

Therefore if you order this from a Japanese calligrapher, expect the first Kanji to look like 温 instead of 溫.

In addition to 温故知新 as mentioned above, this is sometimes written as 温古知新 in Japan.

Clarity

清 is a word that means clarity or clear in Chinese, Japanese Kanji, and old Korean Hanja.

Looking at the parts of this character, you have three splashes of water on the left, “life” on the top right, and the moon on the lower right.

Because of something Confucius said about 2500 years ago, you can imagine that this character means “live life with clarity like bright moonlight piercing pure water.” The Confucian idea is something like “Keep clear what is pure in yourself, and let your pure nature show through.” Kind of like saying, “Don't pollute your mind or body, so that they remain clear.”

This might be stretching the definition of this single Chinese character but the elements are there, and “clarity” is a powerful idea.

Korean note: Korean pronunciation is given above but this character is written with a slight difference in the "moon radical" in Korean. However, anyone who can read Korean Hanja, will understand this character with no problem (this is considered an alternate form in Korean). If you want the more standard Korean Hanja form (which is an alternate form in Chinese), just let me know.

Japanese note: When reading in Japanese, this Kanji has additional meanings of pure, purify, or cleanse (sometimes to remove demons or "exorcise"). Used more in compound words in Japanese than as a stand-alone Kanji.

One Justice Can Overpower 100 Evils

一正压百邪 is an ancient Chinese proverb and idiom that means “One Justice Can Overpower a Hundred Evils.”

While this proverb is famous in China, it has been around so long that its origins have been forgotten.

It could be something that Confucius or one of his disciples said, but no one can say for sure.

Daoism / Taoism

Literally: The Way or Road

道 is the character “dao” which is sometimes written as “tao” but pronounced like “dow” in Mandarin.

道 is the base of what is known as “Taoism.” If you translate this literally, it can mean “the way” or “the path.”

Dao is believed to be that which flows through all things and keeps them in balance. It incorporates the ideas of yin and yang (e.g. there would be no love without hate, no light without dark, no male without female.)

The beginning of Taoism can be traced to a mystical man named

Lao Zi (604-531 BC), who followed, and added to the teachings of Confucius.

More about Taoism / Daoism here.

Note that this is pronounced “dou” and sometimes “michi” when written alone in Japanese but pronounced “do” in word compounds such as Karate-do and Bushido. It's also “do” in Korean.

Alternate translations and meanings: road, way, path; truth, principle province.

Important Japanese note: In Japanese, this will generally be read with the road, way, or path meaning. Taoism is not as popular or well-known in Japan so Daoist/Taoist philosophy is not the first thing a Japanese person will think of when they read this character.

See our Taoism Page

Believe / Faith / Trust

śraddhā

信 can mean to believe, truth, faith, fidelity, sincerity, trust, and confidence in Chinese, old Korean Hanja, and Japanese Kanji.

This single character is often part of other words with similar meanings.

It is one of the five basic tenets of Confucius.

In Chinese, it sometimes has the secondary meaning of a letter (as in the mail) depending on context but it will not be read that way when seen on a wall scroll.

In the Buddhist context, this is śraddhā (faith through hearing or being taught).

Great Aspirations / Ambition

鴻鵠之誌 is a Chinese proverb that implies that having grand ambitions also means that others will not understand your great expectations and ideas.

Though the actual words come from a longer saying of Confucius, which goes, “The little swallows living under the eaves wouldn't understand the lofty ambitions of a swan (who flies far and wide).”

This Confucius quote has led to this idiomatic expression in China that means “think big.” What you'd be saying is “The lofty ambitions of a swan.”

Note that Chinese people sometimes refer to the little swallow as one who does not “think big” but is, instead, stuck in a rut or just leading a mundane life. Therefore, it's a compliment to be called a swan but not a good thing to be called a swallow.

Forgive and Forget

Confucian Proverb

不念舊惡 is a Chinese proverb that can be translated as “Do not recall old grievances,” or more simply as “Forgive and forget.”

The character breakdown:

不 (bù) not; no; don't.

念 (niàn) read aloud.

舊 (jiù) old; former.

惡 (è) wicked deeds; grievances; sins.

This proverb comes from the Analects of Confucius.

Filial Piety

孝 represents filial piety.

Some will define this in more common English as “respect for your parents and ancestors.”

孝 is a subject deeply emphasized by the ancient philosophy and teachings of Confucius.

Some have included this in the list for the Bushido, although generally not considered part of the 7 core virtues of the warrior.

Note: 孝 is not the best of meanings when seen as a single character. Some will read the single-character form to mean “missing my dead ancestors.” However, when written as part of Confucian tenets, or in the two-character word that means filial piety, the meaning is better or read differently (context is important for this character).

We suggest one of our other two-character filial piety entries instead of this one.

Scholar / Confucian

儒 is a unique single character that means scholar or Confucian and leaves a favorable impression when read in Chinese.

Specifically, in Japanese Kanji, this means Confucianism, Confucianist or Chinese scholar.

In old Korean Hanja, this means scholar, Confucian scholar, Confucianist, or learned (one who has learned and knows much).

Basically, it's the same in all three languages.

This in-stock artwork might be what you are looking for, and ships right away...

The following table may be helpful for those studying Chinese or Japanese...

| Title | Characters | Romaji (Romanized Japanese) | Various forms of Romanized Chinese | |

| Confucius | 孔子 | koushi / koshi | kǒng zǐ / kong3 zi3 / kong zi / kongzi | k`ung tzu / kungtzu / kung tzu |

| Confucius: Universal Education | 自行束脩以上吾未嘗無誨焉 (note 嘗 = 嚐) 自行束脩以上吾未尝无诲焉 | zì xíng shù xiū yǐ shàng wú wèi cháng wú huì yān zi4 xing2 shu4 xiu1 yi3 shang4 wu2 wei4 chang2 wu2 hui4 yan1 zi xing shu xiu yi shang wu wei chang wu hui yan | tzu hsing shu hsiu i shang wu wei ch`ang wu hui yen tzu hsing shu hsiu i shang wu wei chang wu hui yen |

|

| The Five Tenets of Confucius | 仁義禮智信 仁义礼智信 | jin gi rei tomo nobu jingireitomonobu | rén yì lǐ zhì xìn ren2 yi4 li3 zhi4 xin4 ren yi li zhi xin renyilizhixin | jen i li chih hsin jenilichihhsin |

| Confucius: Golden Rule Ethic of Reciprocity | 己所不欲勿施於人 己所不欲勿施于人 | jǐ suǒ bú yù wù shī yú rén ji3 suo3 bu2 yu4, wu4 shi1 yu2 ren2 ji suo bu yu, wu shi yu ren jisuobuyu,wushiyuren | chi so pu yü, wu shih yü jen chisopuyü,wushihyüjen |

|

| Benevolence | 仁 | jin | rén / ren2 / ren | jen |

| The Dao of Filial Piety | 孝道 | kou dou / koudou / ko do | xiào dào / xiao4 dao4 / xiao dao / xiaodao | hsiao tao / hsiaotao |

| Respect | 禮 礼 | rei | lǐ / li3 / li | |

| Justice Rectitude Right Decision | 義 义 | gi | yì / yi4 / yi | i |

| Wisdom | 智 | chi / tomo | zhì / zhi4 / zhi | chih |

| The Foundation of Good Conduct | 誌于道據于德依于仁遊于藝 志于道据于德依于仁游于艺 | zhì yú dào jù yú dé yī yú rén yóu yú yì zhi4 yu2 dao4 ju4 yu2 de2 yi1 yu2 ren2 you2 yu2 yi4 zhi yu dao ju yu de yi yu ren you yu yi | chih yü tao chü yü te i yü jen yu yü i | |

| Learning leads to Knowledge, Study leads to Benevolence, Shame leads to Courage | 好學近乎知力行近乎仁知恥近乎勇 好学近乎知力行近乎仁知耻近乎勇 | hào xué jìn hū zhī lì xíng jìn hū rén zhī chǐ jìn hū yǒng hao4 xue2 jin4 hu1 zhi1 li4 xing2 jin4 hu1 ren2 zhi1 chi3 jin4 hu1 yong3 hao xue jin hu zhi li xing jin hu ren zhi chi jin hu yong | hao hsüeh chin hu chih li hsing chin hu jen chih ch`ih chin hu yung hao hsüeh chin hu chih li hsing chin hu jen chih chih chin hu yung |

|

| The Brave Have No Fears | 勇者不懼 勇者不惧 | yuu sha fu ku yuushafuku yu sha fu ku | yǒng zhě bú jù yong3 zhe3 bu2 ju4 yong zhe bu ju yongzhebuju | yung che pu chü yungchepuchü |

| Forgiveness | 恕 | shù / shu4 / shu | ||

| The Ease of the Scholar | 默而識之學而不厭誨人不倦何有于我哉 默而识之学而不厌诲人不倦何有于我哉 | mò ér zhì zhī xué ér bù yàn huǐ rén bù juàn hé yòu yú wǒ zāi mo4 er2 zhi4 zhi1 xue2 er2 bu4 yan4 hui3 ren2 bu4 juan4 he2 you4 yu2 wo3 zai1 mo er zhi zhi xue er bu yan hui ren bu juan he you yu wo zai | mo erh chih chih hsüeh erh pu yen hui jen pu chüan ho yu yü wo tsai | |

| Filial Piety Filial Conduct | 孝行 | koukou / koko | xiào xìng xiao4 xing4 xiao xing xiaoxing | hsiao hsing hsiaohsing |

| Free Will | 自由意志 | jiyuu ishi / jiyuuishi / jiyu ishi | zì yóu yì zhì zi4 you2 yi4 zhi4 zi you yi zhi ziyouyizhi | tzu yu i chih tzuyuichih |

| Learn New Ways From Old Onkochishin | 溫故知新 温故知新 | on ko chi shin onkochishin | wēn gù zhī xīn wen1 gu4 zhi1 xin1 wen gu zhi xin wenguzhixin | wen ku chih hsin wenkuchihhsin |

| Clarity | 清 | sei | qīng / qing1 / qing | ch`ing / ching |

| One Justice Can Overpower 100 Evils | 一正壓百邪 一正压百邪 | yī zhèng yā bǎi xié yi1 zheng4 ya1 bai3 xie2 yi zheng ya bai xie yizhengyabaixie | i cheng ya pai hsieh ichengyapaihsieh |

|

| Daoism Taoism | 道 | michi / -do | dào / dao4 / dao | tao |

| Believe Faith Trust | 信 | shin | xìn / xin4 / xin | hsin |

| Great Aspirations Ambition | 鴻鵠之誌 鸿鹄之志 | hóng hú zhī zhì hong2 hu2 zhi1 zhi4 hong hu zhi zhi honghuzhizhi | hung hu chih chih hunghuchihchih |

|

| Forgive and Forget | 不念舊惡 不念旧恶 | bú niàn jiù è bu2 nian4 jiu4 e4 bu nian jiu e bunianjiue | pu nien chiu o punienchiuo |

|

| Filial Piety | 孝 | kou / ko | xiào / xiao4 / xiao | hsiao |

| Scholar Confucian | 儒 | ju | rú / ru2 / ru | ju |

| In some entries above you will see that characters have different versions above and below a line. In these cases, the characters above the line are Traditional Chinese, while the ones below are Simplified Chinese. | ||||

Successful Chinese Character and Japanese Kanji calligraphy searches within the last few hours...