Many custom options...

And formats...

Home is Where The in Chinese / Japanese...

Buy a Home is Where The calligraphy wall scroll here!

Personalize your custom “Home is Where The” project by clicking the button next to your favorite “Home is Where The” title below...

1. Feel at Ease Anywhere / The World is My Home

7. Welcome Home

11. Home is where the heart is

13. Any success can not compensate for failure in the home

14. Home of the Auspicious Golden Dragon

15. There’s No Place Like Home

18. Hell

19. Sasuga / Takaya

20. Safety and Well-Being of the Family

21. Earth

22. Bones

24. Healthy Living

25. Hung Ga Kuen

26. Roar of Laughter / Big Laughs

27. Choose Life

28. Happy Family

30. Happy Family

31. Forever Family

32. Happy Birthday

34. Divine Grace

35. Nippon Kempo

36. Hung Gar

37. Happy Birthday

38. Feng Shui

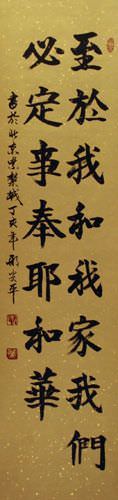

41. Joshua 24:15

42. Hua Mulan

43. Soul Mates

44. Daodejing / Tao Te Ching - Excerpt

45. Confucius: Golden Rule / Ethic of Reciprocity

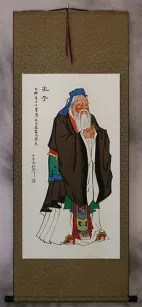

47. Confucius

48. Joshua 24:15

49. Appreciation and Love for Your Parents

50. Unselfish: Perfectly Impartial

Feel at Ease Anywhere / The World is My Home

四海為家 literally reads, “Four Seas Serve-As [my/one's] Home.”

Together, 四海 which literally means “four seas” is understood to mean “the whole world” or “the seven seas.” It's presumed to be an ancient word from back when only four seas were known - so it equates to the modern English term, “seven seas.”

This can be translated or understood in a few different ways:

To regard the four corners of the world all as home.

To feel at home anywhere.

To roam about unconstrained.

To consider the entire country, or the world, to be one's own.

Blessings on this Home

五福臨門 means “five good fortunes arrive [at the] door.”

It is understood to mean “may the five blessings descend upon this home.”

These blessings are known in ancient China to be: longevity, wealth, health, virtue, and natural death (living to old age). This is one of several auspicious sayings you might hear during the Chinese New Year.

Family / Home

家 is the single character that means family in Chinese and Japanese.

It can also mean home or household depending on context.

Hanging this on your wall suggests that you put “family first.”

Pronunciation varies in Japanese depending on context. When pronounced “uchi” in Japanese, it means home, but when pronounced “ke,” it means family.

![]() Note that there is an alternate form of this character. It has an additional radical on the left side but no difference in meaning or pronunciation. The version shown above is the most universal, and is also ancient/traditional. The image shown to the right is only for reference.

Note that there is an alternate form of this character. It has an additional radical on the left side but no difference in meaning or pronunciation. The version shown above is the most universal, and is also ancient/traditional. The image shown to the right is only for reference.

Bless this House

This means “Bless this house” or “Bless this home,” in Japanese.

Some may also translate this as “Bless this family,” since the Kanji for home can also mean family.

Note: Because this selection contains some special Japanese Hiragana characters, it should be written by a Japanese calligrapher.

House of Good Fortune

福宅 is perhaps the Chinese equivalent of “This blessed house” or perhaps “home sweet home.”

This phrase literally means “Good fortune house” or “Good luck household.” It makes any Chinese person who sees it feel that good things happen in the home in which this calligraphy is hung.

No Place Like Home

在家千日好出门一时难 is a Chinese proverb that literally means “At home, one can spend a thousand days in comfort but spending a day away from home can be challenging.”

Figuratively, this means “There's no place like home,” or roughly a Chinese version of “Home sweet home.”

Welcome Home

お帰りなさい is a common Japanese way to say, “welcome home.”

This is said by a person greeting another as they return home. It's a typical phrase that is almost said by reflex as part of Japanese courtesy or etiquette.

Sometimes written as 御帰りなさい (just the first character is Kanji instead of Hiragana).

Note: Because this selection contains some special Japanese Hiragana characters, it should be written by a Japanese calligrapher.

Home of the Dragon

Added by special request of a customer. This phase is natural in Chinese, but it is not a common or ancient title.

The first character is dragon.

The second is a possessive modifier (like making “dragon” into “dragon's”).

The third character means home (but in some context can mean “family” - however, here, it would generally be understood as “home”).

Make Guests Feel at Home

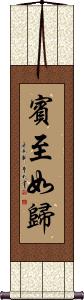

Home away from home

This Chinese phrase suggests that a good host will make guests feel like they are returning home or are as comfortable as they would be at their own homes.

賓至如歸 is also the Chinese equivalent of “a home away from home,” and is used by Chinese hotels, guest houses, and inns to suggest the level of their hospitality that will make you feel at home during your stay.

No Place Like Home

Home is where the heart is

家由心生 is an old Chinese proverb that is roughly equal to the English idiom “Home is where the heart is.”

If you know Chinese, you may recognize the first character as home and the third as the heart.

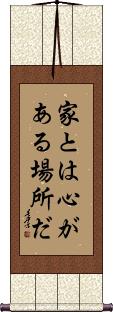

Home is where the heart is

家とは心がある場所だ is, “Home is where the heart is,” in Japanese.

Most Japanese will take this to mean:

If you are with the person or at the place you love most, it becomes your true home.

Note: Because this selection contains some special Japanese Hiragana characters, it should be written by a Japanese calligrapher.

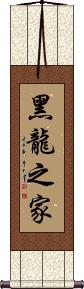

Home of the Black Dragon

黑龍之家 was added by special request of a customer. This phase is natural in Chinese, but it is not a common or ancient title.

The first character is black.

The second is dragon.

The third is a possessive modifier (like making “dragon” into “dragon's”).

The fourth character means home (but in some context can mean “family” - however, here it would generally be understood as “home”).

Any success can not compensate for failure in the home

Home of the Auspicious Golden Dragon

This 金瑞祥龍之家 or “home golden auspicious dragon” title was added by special request of a customer.

The first character means gold or golden.

The second and third characters hold the meaning of auspiciousness and good luck.

The fourth character is dragon.

The fifth is a possessive modifier (like making “dragon” into “dragon's”).

The last character means home (but in some context can mean “family” - however, here it would generally be understood as “home”).

Note: The word order is different than the English title because of grammar differences between English and Chinese. This phrase sounds very natural in Chinese in this character order. If written in the English word order, it would sound very strange and lose its impact in Chinese.

Note: Korean pronunciation is included above, but this has not been reviewed by a Korean translator.

There’s No Place Like Home

金窝银窝不如自己的狗窝 is a Chinese slang proverb that means “Golden house, [or a] silver house, not as good as my own dog house.”

It's basically saying that even a house made of gold or silver is not as good as my own home (which may only be suitable for a dog but at least it's mine).

Family / Household

家庭/傢庭 is a common way to express family, household, or home in Chinese, Japanese Kanji, and old Korean Hanja.

However, for a wall scroll, we recommend the single-character form (which is just the first character of this two-character word). If you want that, just click here: Family Single-Character

The first character means “family” or “home.” The second means “courtyard” or “garden.” When combined, the meaning is a bit different, as it becomes “household” or “family.” The home and/or property traditionally has a strong relationship with family in Asia. Some Chinese, Korean, and Japanese families have lived in the same house for 7 or more generations!

Hell / Judges of Hell

Ancient way to say Hell

陰司 is the ancient way to say “Hell” or “Netherworld” in Chinese.

This title can also refer to the officials of Hell or the judges of Hades or the Netherworld.

Please note that this is a somewhat terrible selection for a wall scroll. Hanging this in your home is like telling the world that your home is hell. Oddly, a lot of people search for this on my website, so I added it for reference.

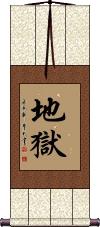

Hell

地獄 is the way that hell is written in modern Chinese, Japanese Kanji, and old Korean Hanja.

There's more than one way to express hell, but this is the one that has stood the test of time.

The first character refers to the ground or the earth.

The second character means jail or prison.

You can also translate this word as infernal, inferno, Hades, or underworld.

It should be noted that this is a somewhat terrible selection for a wall scroll. Hanging this in your home is like telling the world that your home is hell. Oddly, many people search for this on our website, so I added it for reference.

Sasuga / Takaya

Safety and Well-Being of the Family

Kanai Anzen

家內安全 is the Japanese way of saying “Family First.”

It's a Japanese proverb about the safety and well-being of your family and/or peace and prosperity in the household.

Some Japanese will hang an amulet in their home with these Kanji. The purpose is to keep your family safe from harm.

According to Shinto followers, hanging this in your home is seen as an invocation to God to always keep family members free from harm.

We were looking for a way to say “family first” in Japanese when this proverb came up in the conversation and research. While it doesn't say “family first,” it shows that the safety and well-being of your family is your first or most important priority. So, this proverb is the most natural way to express the idea that you put your family first.

See Also: Peace and Prosperity

Earth

地球 is the name of the earth (our planet) in Chinese, old Korean Hanja and Japanese Kanji.

If you love the earth, or want to be reminded of where your home is in the solar system, this is the wall scroll for you.

Bones

骨 is Chinese, Japanese, and Korean for bone or bones.

If your name happens to be Bone or Bones, this is a cool character for a wall scroll to hang in your home or office.

Growing Old Together

偕老 is a Chinese, Japanese, and Korean word that means to grow/growing old together.

This will be a nice wall scroll to hang in your home if your plan is to grow old with your mate.

Healthy Living

If you are into healthy living, 健康生活 might be an excellent selection for a wall scroll to hang in your home.

The first two characters speak of health, vitality, vigor, and being of sound body. The second two characters mean living or life (daily existence).

Hung Ga Kuen

Roar of Laughter / Big Laughs

大笑 can be translated as “roar of laughter,” “loud laughter,” “hearty laugh,” or “cachinnation.”

The first character means big or great, and the second means to laugh or smile.

If you like humor, this is a great wall scroll to hang in your home.

See Also: The Whole Room Rocks With Laughter

Choose Life

選擇生活 can mean to choose life instead of death (or suicide) or to choose to live life to the fullest.

I think of it as the key phrase used by Renton (Ewan McGregor) in the movie Trainspotting. While Chinese people will not think of Trainspotting when they see this phrase, for me, it will always be what comes near the end of this colorful rant:

Choose life. Choose a job. Choose a career. Choose a family. Choose a fucking big television. Choose washing machines, cars, compact disc players, and electrical tin can openers. Choose good health, low cholesterol, and dental insurance. Choose fixed-interest mortgage repayments. Choose a starter home. Choose your friends. Choose leisure wear and matching luggage. Choose a three-piece suite on-hire purchase in a range of fucking fabrics. Choose DIY and wondering who the fuck you are on a Sunday morning. Choose sitting on that couch watching mind-numbing, spirit-crushing game shows, stuffing fucking junk food into your mouth. Choose rotting away at the end of it all, pissing your last in a miserable home, nothing more than an embarrassment to the selfish, fucked-up brats you have spawned to replace yourself. Choose your future. Choose life.

Happy Family

和やかな家庭 means “happy family” or “harmonious family” in Japanese.

The first three Kanji create a word that means mild, calm, gentle, quiet, or harmonious. After that is a connecting article. The last two Kanji mean family, home, or household.

Note: Because this selection contains some special Japanese Hiragana characters, it should be written by a Japanese calligrapher.

Courtesy / Politeness

禮貌 is a Chinese and old Korean word that means courtesy or politeness.

Courtesy is being polite and having good manners. When you speak and act courteously, you give others a feeling of being valued and respected. Greet people pleasantly. Bring courtesy home. Your family needs it most of all. Courtesy helps life to go smoothly.

If you put the words "fēi cháng bù" in front of this, it is like adding "very much not." it’s a great insult in China, as nobody wants to be called "extremely discourteous" or "very much impolite."

Happy Family

和諧之家 means “harmonious family” or “happy family” in Chinese.

The first two characters relay the idea of happiness and harmony.

The third character is a connecting or possessive article (connects harmony/happiness to family).

The last character means family but can also mean home or household.

Forever Family

永遠的家 is a special phrase that we composed for a “family by adoption” or “adoptive family.”

It's the dream of every orphan and foster child to be formally adopted and find their “forever family.”

The first two characters mean forever, eternal, eternity, perpetuity, immortality, and/or permanence. The third character connects this idea with the last character which means “family” and/or “home.”

See Also: Family

Happy Birthday

祝誕生日 is the shortest way to write “Happy Birthday” in Japanese.

The first Kanji means “wish” or “express good wishes,” and the last three characters mean “birthday.”

Because a birthday only lasts one day per year, we strongly suggest that you find an appropriate and personal calligraphy gift that can be hung in the recipient's home year-round.

Family Over Everything

Divine Grace

Nippon Kempo

Hung Gar

洪家 is the martial arts title Hung Ga or Hung Gar.

The first character means flood, big, immense, or great but it can also be the surname, Hong or Hung.

The last character means family or home.

This can also be read as “The Hung Family” or “The Hung Household.” This title is mostly associated with a style of Kung Fu.

Happy Birthday

生日快樂 is how to write “Happy Birthday” in Chinese.

The first two characters mean “birthday,” and the second two characters mean “happiness,” or rather a wish for happiness.

Because a birthday only lasts one day per year, we strongly suggest that you find an appropriate and personal calligraphy gift that can be hung in the recipient's home year-round.

Feng Shui

風水 is the famous technique and approach to arranging your home externally around natural features and internally to create balance and peace.

These two characters literally mean “wind water.” Obviously, the title is far more simple than the concept behind this subject.

It may enlighten you slightly to know that the character for “wind” can also mean style, custom, or manner in some contexts. This may apply somewhat to this title.

In a technical sense, this title is translated as Chinese geomancy.

American Football

美式橄欖球 is the Chinese title for “American football” (not to be confused with international football known as soccer in the USA).

If you are a player or fan of American football, this will make a great wall scroll for your home.

The first two characters mean “American style.”

The last three characters mean football or rugby (a game involving an oblong or ovoid ball).

The “American” adjective is needed in this title to differentiate between Canadian football, Australian rules football, and rugby.

See Also: Soccer

One Family Under Heaven

天下一家 is a proverb that can also be translated as “The whole world is one family.”

It is used to mean that all humans are related by decree of Heaven.

The first two characters can be translated as “the world,” “the whole country,” “descended from heaven,” “earth under heaven,” “the public,” or “the ruling power.”

The second two characters can mean “one family,” “a household,” “one's folks,” “a house” or “a home.” Usually, this is read as “a family.”

Note: This proverb can be understood in Japanese, though not commonly used.

Joshua 24:15

This House Serves the LORD

私と私の家とは、主に仕える is the last bit of Joshua 24:15 in Japanese.

Joshua 24:15 (KJV) ...as for me and my house, we will serve the LORD.

Joshua 24:15 (NIV) ...as for me and my household, we will serve the LORD.

This came from the Shinkaiyaku Japanese Bible. This is the most commonly-used Bible translation in Japan for both Protestants and Catholic Japanese folks.

I think it is a bit like having a secret code on your wall that quietly expresses to whom you are faithful.

This will be a nice gift for a friend or a wonderful expression of faith for your own home.

Note: Because this selection contains some special Japanese Hiragana characters, it should be written by a Japanese calligrapher.

Hua Mulan

花木蘭 is the name of the famous Chinese woman warrior Hua Mulan.

She was made famous in the west by Disney's animated movie, “Mulan.”

Most of the historical information about her comes from an ancient poem. It starts with a concerned Mulan, as she is told a man from each family is to serve conscription in the army. Her father is too old, and her brother is too young. Mulan decides to take the place of her father. After twelve years of war, the army returns, and the best warriors are awarded great posts in the government and riches. Mulan turns down all offers and asks only for a good horse for the long trip home. When Mulan greets visiting comrades wearing her old clothes, they are shocked to find the warrior they rode into battle with for years is actually a woman.

Soul Mates

It was tough to find the best way to say “soul mates” in Chinese. We settled on 天生一對 as an old way to say, “A couple selected by heaven.”

The first two characters together mean “natural” or “innate.” Separated, they mean “heaven” and “born.” The last two characters mean “couple.” So this can be translated as “A couple that is together by nature,” or “A couple brought together by heaven's decree.” With a slight stretch, you could say, “A couple born together from heaven.”

It's a struggle to find the best way to describe this idea in English but trust me, it is pretty cool, and it is a great way to say “soulmates.”

If you're in a happy relationship or marriage and think you have found your soul mate, this would be a wonderful wall scroll to hang in your home.

Daodejing / Tao Te Ching - Excerpt

Excerpt from Chapter 67

一曰慈二曰儉三曰不敢為天下先 is an excerpt from the 67th Chapter of Lao Tzu's (Lao Zi's) Te-Tao Ching (Dao De Jing).

This is the part where the three treasures are discussed. In English, we'd say these three treasures are compassion, frugality, and humility. Some may translate these as love, moderation, and lack of arrogance. I have also seen them translated as benevolence, modesty, and “Not presuming to be at the forefront in the world.” You can mix them up the way you want, as translation is not really a science but rather an art.

I should also explain that the first two treasures are single-character ideas, yet the third treasure was written out in six characters (there are also some auxiliary characters to number the treasures).

If Lao Tzu's words are important to you, then a wall scroll with this passage might make a great addition to your home.

Confucius: Golden Rule / Ethic of Reciprocity

Do not do to others what you do not want done to yourself

Some may think of this as a “Christian trait,” but actually, it transcends many religions.

This Chinese teaching dates back to about 2,500 years ago in China. Confucius had always taught the belief in being benevolent (ren), but this idea was hard to grasp for some of his students, as benevolence could be kind-heartedness or an essence of humanity itself.

When answering Zhong Gong's question as to what "ren" actually meant, Confucius said:

己所不欲勿施于人 or "When you go out, you should behave as if you were in the presence of a distinguished guest; when people do favors for you, act as if a great sacrifice was made for you. Whatever you wouldn't like done to you, do not do that thing to others. Don't complain at work or home.”

Hearing this, Zhong Gong said humbly, “Although I am not clever, I will do what you say.”

From this encounter, the Chinese version of the “Golden Rule” or “Ethic of Reciprocity” came to be.

The characters you see above express, “Do not do to others whatever you do not want to be done to yourself.”

See Also: Confucius Teachings | Benevolence

Wing Chun Fist Maxims (Part 1)

A customer asked me to split these Wing Chun maxims into two parts, so he could order a couplet. I thought this was a good idea, so it's been added here.

1 有手黐手,無手問手

2 來留區送, 甩手直沖

3 怕打終歸打, 貪打終被打

4 粘連迫攻, 絕不放鬆

5 來力瀉力, 借力出擊

A couplet is a set of two wall scrolls that start and finish one phrase or idea. Often, couplets are hung with the first wall scroll on the right side, and the second on the left side of a doorway or entrance. The order in Chinese is right-to-left, so that's why the first wall scroll goes on the right as you face the door.

Of course, couplets can also be hung together on a wall. Often they can be hung to flank an altar, or table with incense, or even flanking a larger central wall scroll. See an example here from the home of Confucius

Be sure to order both parts 1 and 2 together. One without the other is like Eve without Adam.

Confucius

孔子 is how to write the name of the great sage, known in the West as Confucius.

His real name is Kongzi (The name Confucius is a westernized version of his name - his family name is Kong, and “zi” was added as a title of distinction).

He lived some 2500 years ago in Qufu, a town in modern-day Shandong Province of Northern China (about 6 hours south of Beijing by bus). He was a consort to Emperors, and after his death, the impact of his philosophies still served to advise emperors, officials, and common people for generations.

Also during these thousands of years, the Kong family remained powerful in China, and the Kong estate was much like the Vatican in Rome. The Kong estate existed as if on sovereign ground with its own small garrison of guards and the privileges of a kingdom within an empire.

This was true up until the time the Kong family had to flee to Taiwan in 1949 when the Red Army took victory over the Nationalists during the Revolution. The home of Confucius was later razed and all statues were defaced or stolen during the Cultural Revolution. Finally, after years of smearing his name and image, it is once again okay to celebrate the teachings of Confucius in mainland China.

Known as Khổng Tử in Vietnamese.

Joshua 24:15

This House Serves the LORD

至於我和我家我們必定事奉耶和華 is the last sentence of Joshua 24:15 in Chinese.

What your

calligraphy

might look like

from our

Chinese Master

Calligrapher

Joshua 24:15 (KJV) ...as for me and my house, we will serve the LORD.

Joshua 24:15 (NIV) ...as for me and my household, we will serve the LORD.

We used the only official Christian Chinese Bible that I know of so that the translation would be as accurate and standard as possible. Any Chinese Christian worth their salt will easily be able to identify this verse from the Chinese words on this scroll.

I think it is a bit like having a secret code on your wall that quietly expresses to whom you are faithful.

A great gift for your devout Christian or Jewish friend if they happen to be fond of Asian art.

Or perhaps a wonderful “conversation starter” for your own home.

Note: If you are curious, the last three characters represent the way “LORD” is used in most English Bibles. In Chinese, this is actually the phonetic name from Mandarin Chinese for “Jehovah.”

Appreciation and Love for Your Parents

誰言寸草心報得三春暉 is the last line of a famous poem. It is perceived as a tribute or ode to your parents or mother from a child or children that have left home.

The poem was written by Meng Jiao during the Tang Dynasty (about 1200 years ago). The Chinese title is “You Zi Yin” which means “The Traveler's Recite.”

The last line as shown here speaks of the generous and warm spring sunlight which gives the grass far beyond what the little grass can could ever give back (except perhaps by showing its lovely green leaves and flourishing). The metaphor is that the sun is your mother or parents, and you are the grass. Your parents raise you and give you all the love and care you need to prepare you for the world. A debt that you can never repay, nor is repayment expected.

The first part of the poem (not written in the characters to the left) suggests that the thread in a loving mother's hands is the shirt of her traveling offspring. Vigorously sewing while wishing them to come back sooner than they left.

...This part is really hard to translate into English that makes any sense but maybe you get the idea. We are talking about a poem that is so old that many Chinese people would have trouble reading it (as if it was the King James Version of Chinese).

Unselfish: Perfectly Impartial

大公無私 is a Chinese proverb that comes from an old story from some time before 476 BC. About a man named Qi Huangyang, who was commissioned by the king to select the best person for a certain job in the Imperial Court.

Qi Huangyang selected his enemy for the job. The king was very confused by the selection, but Qi Huangyang explained that he was asked to find the best person for the job, not necessarily someone that he liked or had a friendship with.

Later, Confucius commented on how unselfish and impartial Qi Huangyang was by saying, “Da Gong Wu Si” which, if you look it up in a Chinese dictionary, is generally translated as “Unselfish” or “Just and Fair.”

If you translate each character, you'd have something like

“Big/Deep Justice Without Self.”

Direct translations like this leave out a lot of what the Chinese characters really say. Use your imagination, and suddenly you realize that “without self” means “without thinking about yourself in the decision” - together, these two words mean “unselfish.” The first two characters serve to drive the point home that we are talking about a concept that is similar to “blind justice.”

One of my Chinese-English dictionaries translates this simply as “just and fair.” So that is the short and simple version.

Note: This can be pronounced in Korean, but it's not a commonly used term.

See Also: Selflessness | Work Unselfishly for the Common Good | Altruism

Undaunted After Repeated Setbacks

Persistence to overcome all challenges

百折不撓 is a Chinese proverb that means “Be undaunted in the face of repeated setbacks.”

More directly translated, it reads, “[Overcome] a hundred setbacks, without flinching.” 百折不撓 is of Chinese origin but is commonly used in Japanese and somewhat in Korean (same characters, different pronunciation).

This proverb comes from a long, and occasionally tragic story of a man that lived sometime around 25-220 AD. His name was Qiao Xuan, and he never stooped to flattery but remained an upright person at all times. He fought to expose the corruption of higher-level government officials at great risk to himself.

Then when he was at a higher level in the Imperial Court, bandits were regularly capturing hostages and demanding ransoms. But when his own son was captured, he was so focused on his duty to the Emperor and the common good that he sent a platoon of soldiers to raid the bandits' hideout, and stop them once and for all even at the risk of his own son's life. While all of the bandits were arrested in the raid, they killed Qiao Xuan's son at first sight of the raiding soldiers.

Near the end of his career, a new Emperor came to power, and Qiao Xuan reported to him that one of his ministers was bullying the people and extorting money from them. The new Emperor refused to listen to Qiao Xuan and even promoted the corrupt Minister. Qiao Xuan was so disgusted that in protest, he resigned from his post as minister (something almost never done) and left for his home village.

His tombstone reads “Bai Zhe Bu Nao” which is now a proverb used in Chinese culture to describe a person of strong will who puts up stubborn resistance against great odds.

My Chinese-English dictionary defines these 4 characters as “keep on fighting despite all setbacks,” “be undaunted by repeated setbacks,” and “be indomitable.”

Our translator says it can mean “never give up” in modern Chinese.

Although the first two characters are translated correctly as “repeated setbacks,” the literal meaning is “100 setbacks” or “a rope that breaks 100 times.” The last two characters can mean “do not yield” or “do not give up.”

Most Chinese, Japanese, and Korean people will not take this absolutely literal meaning but will instead understand it as the title suggests above. If you want a single big word definition, it would be indefatigability, indomitableness, persistence, or unyielding.

See Also: Tenacity | Fortitude | Strength | Perseverance | Persistence

Mountain Travels Poem by Dumu

This poem was written almost 1200 years ago during the Tang dynasty.

It depicts traveling up a place known as Cold Mountain, where some hearty people have built their homes. The traveler is overwhelmed by the beauty of the turning leaves of the maple forest that surrounds him just as night overtakes the day, and darkness prevails. His heart implores him to stop, and take in all of the beauty around him.

First, before you get to the full translation, I must tell you that Chinese poetry is a lot different than what we have in the west. Chinese words simply don't rhyme in the same way that English or other western languages do. Chinese poetry depends on rhythm and a certain beat of repeated numbers of characters.

I have done my best to translate this poem keeping a certain feel of the original poet. But some of the original beauty of the poem in its original Chinese will be lost in translation.

Far away on Cold Mountain, a stone path leads upwards.

Among white clouds, people's homes reside.

Stopping my carriage I must, as to admire the maple forest at nights fall.

In awe of autumn leaves showing more red than even flowers of early spring.

Hopefully, this poem will remind you to stop, and “take it all in” as you travel through life.

The poet's name is “Du Mu” in Chinese that is: ![]()

![]() .

.

The title of the poem, “Mountain Travels” is: ![]()

![]()

You can have the title, poet's name, and even “Tang Dynasty” written as an inscription on your custom wall scroll if you like.

More about the poet:

Dumu lived from 803-852 AD and was a leading Chinese poet during the later part of the Tang dynasty.

He was born in Chang'an, a city in central China and the former capital of the ancient Chinese empire in 221-206 BC. In present-day China, his birthplace is currently known as Xi'an, the home of the Terracotta Soldiers.

He was awarded his Jinshi degree (an exam administered by the emperor's court which leads to becoming an official of the court) at the age of 25 and went on to hold many official positions over the years. However, he never achieved a high rank, apparently because of some disputes between various factions, and his family's criticism of the government. His last post in the court was his appointment to the office of Secretariat Drafter.

During his life, he wrote scores of narrative poems, as well as a commentary on the Art of War and many letters of advice to high officials.

His poems were often very realistic and often depicted everyday life. He wrote poems about everything, from drinking beer in a tavern to weepy poems about lost love.

The thing that strikes you most is the fact even after 1200 years, not much has changed about the beauty of nature, toils, and troubles of love and beer drinking.

This in-stock artwork might be what you are looking for, and ships right away...

Gallery Price: $100.00

Your Price: $49.77

Chinese Village Home Landscape Painting

Discounted Blemished

Gallery Price: $90.00

Your Price: $49.00

Gallery Price: $120.00

Your Price: $79.88

Gallery Price: $400.00

Your Price: $188.88

Gallery Price: $400.00

Your Price: $188.88

Gallery Price: $400.00

Your Price: $138.88

Gallery Price: $61.00

Your Price: $33.88

Gallery Price: $72.00

Your Price: $39.88

Gallery Price: $60.00

Your Price: $36.88

Gallery Price: $60.00

Your Price: $36.88

Gallery Price: $286.00

Your Price: $158.88

The following table may be helpful for those studying Chinese or Japanese...

| Title | Characters | Romaji (Romanized Japanese) | Various forms of Romanized Chinese | |

| Feel at Ease Anywhere The World is My Home | 四海為家 四海为家 | sì hǎi wéi jiā si4 hai3 wei2 jia1 si hai wei jia sihaiweijia | ssu hai wei chia ssuhaiweichia |

|

| Blessings on this Home | 五福臨門 五福临门 | wǔ fú lín mén wu3 fu2 lin2 men2 wu fu lin men wufulinmen | ||

| Family Home | 家 / 傢 家 | ei / uchi / ke | jiā / jia1 / jia | chia |

| Bless this House | この家に祝福を | kono-ka ni shukufuku o kono-kanishukufukuo | ||

| House of Good Fortune | 福宅 | fú zhái / fu2 zhai2 / fu zhai / fuzhai | fu chai / fuchai | |

| No Place Like Home | 在家千日好出門一時難 在家千日好出门一时难 | zài jiā qiān rì hǎo chū mén yì shí nán zai4 jia1 qian1 ri4 hao3 chu1 men2 yi4 shi2 nan2 zai jia qian ri hao chu men yi shi nan | tsai chia ch`ien jih hao ch`u men i shih nan tsai chia chien jih hao chu men i shih nan |

|

| Welcome Home | お帰りなさい | okaerinasai | ||

| Home of the Dragon | 龍之家 龙之家 | lóng zhī jiā long2 zhi1 jia1 long zhi jia longzhijia | lung chih chia lungchihchia |

|

| Make Guests Feel at Home | 賓至如歸 宾至如归 | bīn zhì rú guī bin1 zhi4 ru2 gui1 bin zhi ru gui binzhirugui | pin chih ju kuei pinchihjukuei |

|

| No Place Like Home | 故郷忘じ難し | kokyouboujigatashi kokyobojigatashi | ||

| Home is where the heart is | 家由心生 | jiā yóu xīn shēng jia1 you2 xin1 sheng1 jia you xin sheng jiayouxinsheng | chia yu hsin sheng chiayuhsinsheng |

|

| Home is where the heart is | 家とは心がある場所だ | ie to wa kokoro ga aru basho da ietowakokorogaarubashoda | ||

| Home of the Black Dragon | 黑龍之家 黑龙之家 | hēi lóng zhī jiā hei1 long2 zhi1 jia1 hei long zhi jia heilongzhijia | hei lung chih chia heilungchihchia |

|

| Any success can not compensate for failure in the home | 所有的成功都無法補償家庭的失敗 所有的成功都无法补偿家庭的失败 | suǒ yǒu de chéng gōng dōu wú fǎ bǔ cháng jiā tíng de shī bài suo3 you3 de cheng2 gong1 dou1 wu2 fa3 bu3 chang2 jia1 ting2 de shi1 bai4 suo you de cheng gong dou wu fa bu chang jia ting de shi bai | so yu te ch`eng kung tou wu fa pu ch`ang chia t`ing te shih pai so yu te cheng kung tou wu fa pu chang chia ting te shih pai |

|

| Home of the Auspicious Golden Dragon | 金瑞祥龍之家 金瑞祥龙之家 | jīn ruì xiáng lóng zhī jiā jin1 rui4 xiang2 long2 zhi1 jia1 jin rui xiang long zhi jia jinruixianglongzhijia | chin jui hsiang lung chih chia | |

| There’s No Place Like Home | 金窩銀窩不如自己的狗窩 金窝银窝不如自己的狗窝 | jīn wō yín wō bù rú zì jǐ de gǒu wō jin1 wo1 yin2 wo1 bu4 ru2 zi4 ji3 de5 gou3 wo1 jin wo yin wo bu ru zi ji de gou wo | chin wo yin wo pu ju tzu chi te kou wo | |

| Family Household | 家庭 / 傢庭 家庭 | ka tei / katei | jiā tíng / jia1 ting2 / jia ting / jiating | chia t`ing / chiating / chia ting |

| Hell Judges of Hell | 陰司 阴司 | yīn sī / yin1 si1 / yin si / yinsi | yin ssu / yinssu | |

| Hell | 地獄 地狱 | jigoku | dì yù / di4 yu4 / di yu / diyu | ti yü / tiyü |

| Sasuga Takaya | 貴家 | takaya / takatsuka / sasuga / kiya / kika | ||

| Safety and Well-Being of the Family | 家內安全 家内安全 | ka nai an zen kanaianzen | ||

| Earth | 地球 | chi kyuu / chikyuu / chi kyu | dì qiú / di4 qiu2 / di qiu / diqiu | ti ch`iu / tichiu / ti chiu |

| Bones | 骨 | hone / kotsu | gǔ / gu3 / gu | ku |

| Growing Old Together | 偕老 | kairou / kairo | xié lǎo / xie2 lao3 / xie lao / xielao | hsieh lao / hsiehlao |

| Healthy Living | 健康生活 | kenkou seikatsu kenkouseikatsu kenko seikatsu | jiàn kāng shēng huó jian4 kang1 sheng1 huo2 jian kang sheng huo jiankangshenghuo | chien k`ang sheng huo chienkangshenghuo chien kang sheng huo |

| Hung Ga Kuen | 洪家拳 | hóng jiā quán hong2 jia1 quan2 hong jia quan hongjiaquan | hung chia ch`üan hungchiachüan hung chia chüan |

|

| Roar of Laughter Big Laughs | 大笑 | taishou / taisho | dà xiào / da4 xiao4 / da xiao / daxiao | ta hsiao / tahsiao |

| Choose Life | 選擇生活 选择生活 | xuǎn zé shēng huó xuan3 ze2 sheng1 huo2 xuan ze sheng huo xuanzeshenghuo | hsüan tse sheng huo hsüantseshenghuo |

|

| Happy Family | 和やかな家庭 | nago ya ka na ka tei nagoyakanakatei | ||

| Courtesy Politeness | 禮貌 礼貌 | lǐ mào / li3 mao4 / li mao / limao | ||

| Happy Family | 和諧之家 和谐之家 | hé xié zhī jiā he2 xie2 zhi1 jia1 he xie zhi jia hexiezhijia | ho hsieh chih chia hohsiehchihchia |

|

| Forever Family | 永遠的家 永远的家 | yǒng yuǎn de jiā yong3 yuan3 de jia1 yong yuan de jia yongyuandejia | yung yüan te chia yungyüantechia |

|

| Happy Birthday | 祝誕生日 | shuku tan jou bi shukutanjoubi shuku tan jo bi | ||

| Family Over Everything | 家庭至上 | jiā tíng zhì shàng jia1 ting2 zhi4 shang4 jia ting zhi shang jiatingzhishang | chia t`ing chih shang chiatingchihshang chia ting chih shang |

|

| Divine Grace | 天佑 | ten yuu / tenyuu / ten yu | tiān yòu / tian1 you4 / tian you / tianyou | t`ien yu / tienyu / tien yu |

| Nippon Kempo | 日本拳法 | nippon kenpou / nihon kenpou nipon kenpo / nihon kenpo | ||

| Hung Gar | 洪家 | hóng jiā / hong2 jia1 / hong jia / hongjia | hung chia / hungchia | |

| Happy Birthday | 生日快樂 生日快乐 | shēng rì kuài lè sheng1 ri4 kuai4 le4 sheng ri kuai le shengrikuaile | sheng jih k`uai le shengjihkuaile sheng jih kuai le |

|

| Feng Shui | 風水 风水 | fuu sui / fuusui / fu sui | fēng shuǐ feng1 shui3 feng shui fengshui | |

| American Football | 美式橄欖球 美式橄榄球 | měi shì gǎn lǎn qiú mei3 shi4 gan3 lan3 qiu2 mei shi gan lan qiu meishiganlanqiu | mei shih kan lan ch`iu meishihkanlanchiu mei shih kan lan chiu |

|

| One Family Under Heaven | 天下一家 | tenka ikka / tenkaikka / tenka ika | tiān xià yī jiā tian1 xia4 yi1 jia1 tian xia yi jia tianxiayijia | t`ien hsia i chia tienhsiaichia tien hsia i chia |

| Joshua 24:15 | 私と私の家とは主に仕える | Watashi to watashinoie to wa omo ni tsukaeru | ||

| Hua Mulan | 花木蘭 花木兰 | huā mù lán hua1 mu4 lan2 hua mu lan huamulan | ||

| Soul Mates | 天生一對 天生一对 | tiān shēng yí duì tian1 sheng1 yi2 dui4 tian sheng yi dui tianshengyidui | t`ien sheng i tui tienshengitui tien sheng i tui |

|

| Daodejing Tao Te Ching - Excerpt | 一曰慈二曰儉三曰不敢為天下先 一曰慈二曰俭三曰不敢为天下先 | yī yuē cí èr yuē jiǎn sān yuē bù gǎn wéi tiān xià xiān yi1 yue1 ci2 er4 yue1 jian3 san1 yue1 bu4 gan3 wei2 tian1 xia4 xian1 yi yue ci er yue jian san yue bu gan wei tian xia xian | i yüeh tz`u erh yüeh chien san yüeh pu kan wei t`ien hsia hsien i yüeh tzu erh yüeh chien san yüeh pu kan wei tien hsia hsien |

|

| Confucius: Golden Rule Ethic of Reciprocity | 己所不欲勿施於人 己所不欲勿施于人 | jǐ suǒ bú yù wù shī yú rén ji3 suo3 bu2 yu4, wu4 shi1 yu2 ren2 ji suo bu yu, wu shi yu ren jisuobuyu,wushiyuren | chi so pu yü, wu shih yü jen chisopuyü,wushihyüjen |

|

| Wing Chun Fist Maxims (Part 1) | 有手黐手無手問手來留區送甩手直沖怕打終歸打貪打終被打粘連迫攻絕不放鬆來力瀉力借力出擊 有手黐手无手问手来留区送甩手直冲怕打终归打贪打终被打粘连迫攻绝不放松来力泻力借力出击 | |||

| Confucius | 孔子 | koushi / koshi | kǒng zǐ / kong3 zi3 / kong zi / kongzi | k`ung tzu / kungtzu / kung tzu |

| Joshua 24:15 | 至於我和我家我們必定事奉耶和華 至于我和我家我们必定事奉耶和华 | zhì yú wǒ hé wǒ jiā wǒ men bì dìng shì fèng yē hé huá zhi4 yu2 wo3 he2 wo3 jia1 wo3 men bi4 ding4 shi4 feng4 ye1 he2 hua2 zhi yu wo he wo jia wo men bi ding shi feng ye he hua | chih yü wo ho wo chia wo men pi ting shih feng yeh ho hua | |

| Appreciation and Love for Your Parents | 誰言寸草心報得三春暉 谁言寸草心报得三春晖 | shuí yán cùn cǎo xīn bào dé sān chūn huī shui2 yan2 cun4 cao3 xin1 bao4 de2 san1 chun1 hui1 shui yan cun cao xin bao de san chun hui | shui yen ts`un ts`ao hsin pao te san ch`un hui shui yen tsun tsao hsin pao te san chun hui |

|

| Unselfish: Perfectly Impartial | 大公無私 大公无私 | dà gōng wú sī da4 gong1 wu2 si1 da gong wu si dagongwusi | ta kung wu ssu takungwussu |

|

| Undaunted After Repeated Setbacks | 百折不撓 百折不挠 | hyaku setsu su tou hyakusetsusutou hyaku setsu su to | bǎi zhé bù náo bai3 zhe2 bu4 nao2 bai zhe bu nao baizhebunao | pai che pu nao paichepunao |

| Mountain Travels Poem by Dumu | 遠上寒山石徑斜白雲生處有人家停車坐愛楓林晚霜葉紅於二月花 远上寒山石径斜白云生处有人家停车坐爱枫林晚霜叶红于二月花 | yuǎn shàng hán shān shí jìng xiá bái yún shēng chù yǒu rén jiā tíng chē zuò ài fēng lín wǎn shuàng yè hóng yú èr yuè huā yuan3 shang4 han2 shan1 shi2 jing4 xia2 bai2 yun2 sheng1 chu4 you3 ren2 jia1 ting2 che1 zuo4 ai4 feng1 lin2 wan3 shuang4 ye4 hong2 yu2 er4 yue4 hua1 yuan shang han shan shi jing xia bai yun sheng chu you ren jia ting che zuo ai feng lin wan shuang ye hong yu er yue hua | yüan shang han shan shih ching hsia pai yün sheng ch`u yu jen chia t`ing ch`e tso ai feng lin wan shuang yeh hung yü erh yüeh hua yüan shang han shan shih ching hsia pai yün sheng chu yu jen chia ting che tso ai feng lin wan shuang yeh hung yü erh yüeh hua |

|

| In some entries above you will see that characters have different versions above and below a line. In these cases, the characters above the line are Traditional Chinese, while the ones below are Simplified Chinese. | ||||

Successful Chinese Character and Japanese Kanji calligraphy searches within the last few hours...