48¾"

20"

Approximate Measurements

Artwork Panel: 32.3cm x 68.5cm ≈ 12¾" x 27"

Silk/Brocade: 41.6cm x 124cm ≈ 16¼" x 48¾"

Width at Wooden Knobs: 50.6cm ≈ 20"

Close up view of the artwork mounted to this silk brocade wall scroll

-OR- It's Never Too Late Too Mend

If you want to know the real story behind this Chinese proverb, read below...

Long ago in what is now China, there were many kingdoms throughout the land. This time period is known as The Warring States Period by historians because these kingdoms often did not get along with each other.

Some time around 279 B.C. the Kingdom of Chu was a large, but not particularly powerful kingdom. Part of the reason it lacked power was the fact that the King was surrounded by "yes men" who told him only what he wanted to hear. Many of the King's court officials were corrupt and incompetent which did not help the situation.

The King was not blameless himself, as he started spending much of his time being entertained by his many concubines.

One of the King's ministers named Zhuang Xin saw problems on the horizon for the Kingdom, and warned the King, "Your Majesty, you are surrounded by people who tell you what you want to hear. They tell you things to make you happy, and cause you to ignore important state affairs. If this is allowed to continue, the Kingdom of Chu will surely perish, and fall into ruins".

This enraged the King who scolded Zhuang Xin for insulting the country and accused him of trying to create resentment among the people.

Zhuang Xin explained, "I dare not curse the Kingdom of Chu, but I feel that we face great danger in the future because of the current situation".

The King was not impressed with Zhuang Xin's words.

Seeing the King's displeasure with him and the King's fondness for his court of corrupt officials, Zhuang Xin asked permission of the King that he may take leave of the Kingdom of Chu, and travel to the State of Zhao to live. The King agreed, and Zhuang Xin left the Kingdom of Chu, perhaps forever.

Five months later, troops from the neighboring Kingdom of Qin invaded Chu, taking a huge tract of land. The King of Chu went into exile, and it appeared that soon, the Kingdom of Chu would no longer exist.

The King of Chu remembered the words of Zhuang Xin, and sent some of his men to find him. Immediately, Zhuang Xin returned to meet the King. The first question asked by the King was, "What can I do now".

Zhuang Xin told the King this story:

A shepherd woke one morning to find a sheep missing. Looking at the pen saw a hole in the fence where a wolf had come through to steal one of his sheep. His friends told him that he had best fix the hole at once. But the Shepard thought since the sheep is already gone, there is no use fixing the hole.

The next morning, another sheep was gone. And the Shepard realized that he must mend the fence at once. Zhuang Xin then went on to make suggestions about what could be done to reclaim the land lost to the Kingdom of Qin, and reclaim the former glory and integrity in the Kingdom of Chu.

The idiom  came from this reply from

Zhuang Xin to the King of Chu almost 2,300 years ago.

came from this reply from

Zhuang Xin to the King of Chu almost 2,300 years ago.

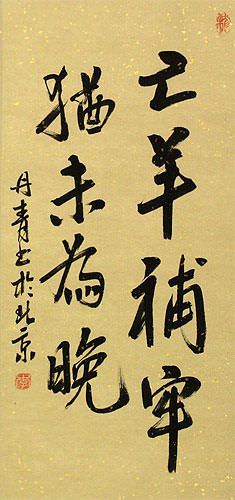

It translates roughly into English as...

This phrase is often used in modern China when suggesting in a hopeful way that someone change their ways, or fix something in their life. It might be used to suggest fixing a marriage, quitting smoking, or getting back on track after taking an unfortunate path in life among other things one might fix in their life.

I suppose in the same way that we might say",Today is the first day of the rest of your life" in our western cultures to suggest that you can always start anew.

This calligraphy was created by Li Dan-Qing of Beijing. He's an older gentleman who has been involved with the art community of China, all of his life. Now in retirement, he creates calligraphy for us for sort of "hobby income".

The calligraphy was done using black Chinese ink on xuan paper (known incorrectly in the west as "rice paper"). The raw artwork was then taken to our Wall Scroll Workshop where it was laminated to more sheets of xuan paper, and built into a beautiful silk brocade wall scroll. Except for the use of a lathe to turn the wooden knobs, this wall scroll is virutally 100% handmade from start to finish (even the paper is made by hand).